Making the Party Fun Again: The Shifting Landscape of Our Film and TV Ecosystem — Part 1

How did we get here? Where is it going?

You want to pay for another streaming service? Do you feel anxious when asked to sort through even more content? The answer is yes, of course.

Nevertheless, film and TV providers still try to lure you into a tangle of platforms and subscriptions so complicated you need a forensic accountant to analyze your monthly statement.

But everyone must keep up. “There’s a lot of good content out there,” they all say. In fact, some films and shows are mind-blowingly excellent, but you can’t always find what you’re looking for or afford the costs involved. It’s like being at a party jam-packed with the greatest artists and entertainers alive. You want to interact with everyone, moving easily from table to table, but the crowds and noise prove too much. You resign yourself to engaging with whomever you first recognize, all the while wondering what you're missing. Then, the bill comes.

Could there be a better way? As equal parts industry observer and fellow audience member, I think it pays to examine the trajectory of the streaming era and what it signals for the future of the film and TV ecosystem.

There are other readings on this topic, but I often long for a more thorough review to orient my inundated brain as to what the hell has exactly happened over the last twenty-five years—and, importantly, what matters most at this transformative point in the industry’s history. We’re sprinting through this already overwhelmed century, and I’m trying to make sense of the substantive versus the not so much, especially when it comes to the state of entertainment and our hypermediated culture more broadly.

Accordingly, this is the first installment of a 4-part series to help get our bearings on the streaming film and TV industry. The series will cover the following:

Revisiting the transition from the dominance of linear TV and theater to the ascendancy of streaming platforms (that’s the entry you’re reading now)

What audiences report wanting (and not wanting)

Looming industry consolidation and simplification

Possible improvements and challenges in the years ahead

Let’s take stock. Indulge with me.

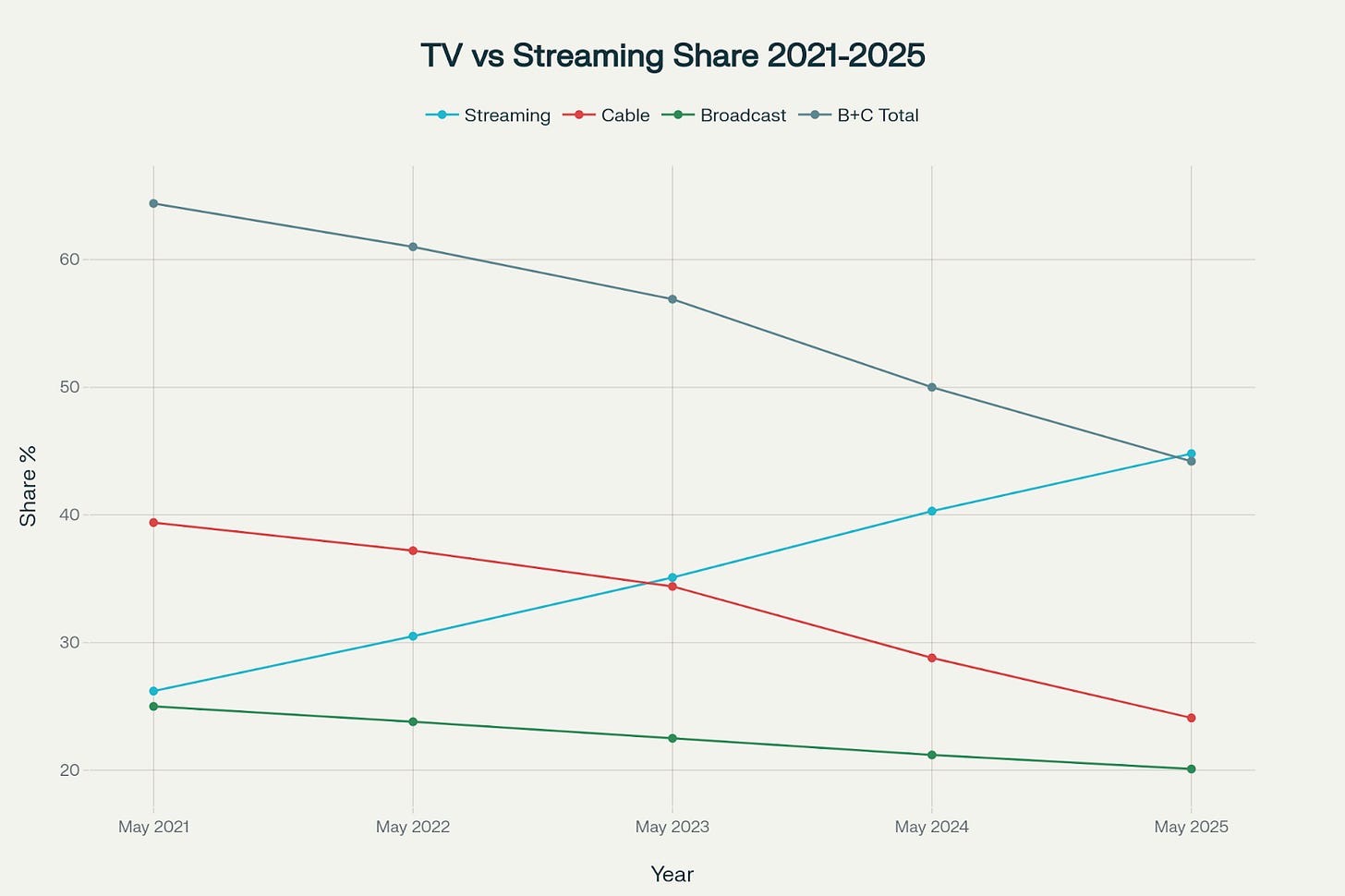

Acronym Soup

We are now a few decades into the era of big tech transforming Hollywood. Gone are the days of studio and cable company dominance. This is the heyday of Squid Game, KPop Demon Hunters and Mr. Beast. In May 2025, the streaming industry, valued at over $108 billion, hit a significant milestone that many would have thought absurd just a few years ago: streaming won the battle for TV viewership, capturing 44.8% of total TV usage compared to 44.2% for broadcast and cable television combined.1,2 Annual revenue by the end of 2025 is expected to show a nearly 7% annual growth rate with a projected 2030 market value of $164.41 billion.3 This didn’t happen overnight…but nearly so. From 2021 to 2025, streaming usage increased globally by an estimated 71% through the proliferation of at least 200 distinct platforms; some sources estimate that the total number of active streaming services could be even higher, perhaps amounting to more than 400 worldwide. 4,5

Netflix and YouTube (Alphabet/Google) preside as indisputable giants. In Q4 2024, Netflix reported 301.6 million subscribers. YouTube touts a staggering 2.7 billion monthly active users and accumulates approximately 3.8 billion unique visitors and hundreds of billions of views monthly.6,7 Other key players in the field stand (with varying success) as the outcome of Old Hollywood attempting to meld with corporate goliaths. The usual suspects are present here: Apple, Amazon (Prime Video), Disney, Fox, NBCUniversal, Warner Bros. Discovery, and Paramount/Skydance. There are also a slew of additional providers and subsidiaries ranging from AMC to The Criterion Collection to ViX that cater to more targeted, demographic-specific or genre-oriented audience segments.

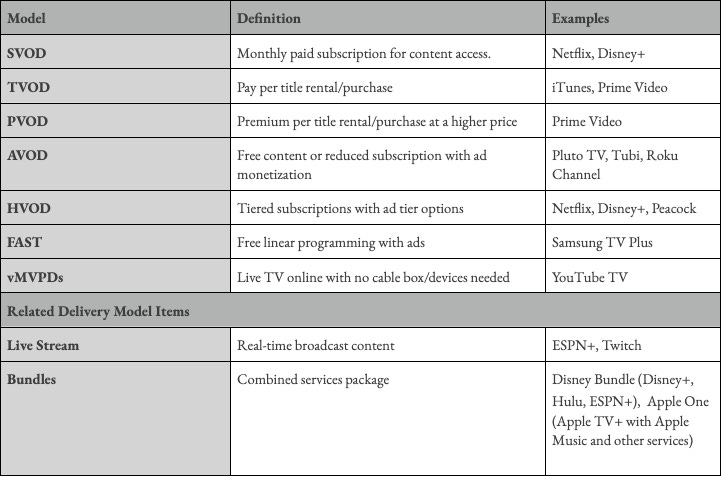

To reach audiences, these streaming providers serve content in myriad, sometimes perplexing ways. The primary delivery models are legion: Streaming Video on Demand (SVOD), Transaction Video on Demand (TVOD), Premium Video on Demand (PVOD), Advertising Video on Demand (AVOD), Hybrid Video on Demand (HVOD), Free Ad-supported Streaming Television (FAST), and Virtual Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (vMVPDs). All these acronyms strung together may sound like various strains of a rare communicable disease, or cue you to scream WTFOD…and I may not have catalogued all of them.

Quick glossary of sorts:

If you go outside of the U.S., the complexity magnifies. Market-specific platforms may only be offered in certain countries. International streaming giants often also piggyback on popular over-the-air providers, combining forces and bundling options with regional cable companies. Approximately 1 in 3 streaming services have established partnerships with regional over-the-air and Pay TV providers, and up to 77.9% of these alliances are with telecom and Pay TV operators. Commercial bundles represent 63.7% of the collaborations, especially in regions like Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA), Asia-Pacific (APAC), and Latin America (LATAM), with local giants (e.g., Vodafone, Orange, Telia, Claro, VIVO) hosting partnerships with Netflix, HBO Max, Disney+, and Prime Video.9

There’s also the sometimes overlooked role of TV and device manufacturers, such as Samsung TV, Amazon Fire Stick and Roku, getting into the mix with operating systems (OS) and platforms granting access to a range of third-party streaming apps and FAST channels (e.g., Prime Video offering access to Apple+ or AMC ‘channels’ for an additional cost).6

It's a convoluted global market saturated with options.

Though the next post will get more in-depth on how this registers with audiences, suffice it to say that people must navigate a ‘room packed beyond capacity’. The related phenomena of so-called consumer ‘choice paralysis’ and ‘subscription fatigue’ are real. It is not a sustainable state of affairs.

Still, to understand how we arrived at this complicated streaming context, it is necessary to remember what we were trying to leave behind. What were the incentives for choosing streaming services, anyway? This is where we revisit cable TV and the movie theater experience before the rise of Netflix, YouTube, and the many platforms that followed.

Cable’s Appointment Viewing or Anything You Want?

Remember when cable TV dominated home entertainment? At its height between 2000-2010, cable reached over 105 million pay-TV households (cable plus satellite), which equated to 90% penetration of U.S. TV homes.10,11 By 2013, the average household received 189 channels (though viewers typically reported watching only about 17 channels). Cable also offered access to exclusive and niche content compared to the scant channels available through over-the-air broadcast (VHF/UHF). Popular channels like HBO, ESPN, MTV, Nickelodeon, and CNN provided premium, news, niche, and live content unavailable elsewhere. Also, the 1990s-2010s saw cable networks release widely acclaimed original series made with a degree of creative freedom and ambition largely unknown to the broadcast networks. Scripted shows like The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad elevated television to a level of artistry previously associated only with feature film culture. By 2015, cable networks produced 189 scripted shows compared to broadcast TV's 119. Abundance, speciality and creativity characterized this new peak in TV programming.10

Viewers also came to expect a user experience vastly improved from the TV standards of past decades. Premium channels like HBO offered commercial-free viewing, a welcome improvement over ad after ad disrupting cinematic flow. Payment was simple, too. One monthly bill—commonly bundled with internet and phone service for integrated convenience—covered dozens of channels, with all content accessible through a single interface and remote control.

But people started to grumble. While the payment process was straightforward, cable bills could exceed $100 per month when accounting for forced bundling of unwanted channels, equipment rental fees, and hidden charges. Also, outside of premium options like HBO and Showtime, most channels afforded limited creative leeway to content makers and often interrupted programming with commercials, as networks were still beholden to advertiser requirements and traditional approval standards. The user experience suffered as a consequence. Compounding these problems, the glut of channel offerings made locating content inefficient and time-consuming.

Finally, constraints on when and how audiences could view content proved to be the most crucial drawback. Cable and broadcast TV were linear and aired on a set schedule. This required viewers to coordinate their day around primetime television. The situation also forced people to be home at designated times to watch their favorite shows unless they had DVRs to record shows. However, even this technology required a waiting period between episodes. At a time when the burgeoning internet had begun to train people on grabbing information whenever they wanted, such a condition of ‘wait-to-see’ gradually became untenable and antiquated for impatient audiences.

Multiplex Versus Multiscreen

“I strongly believe the future of cinema will be on the big screen, no matter what any Wall Street dilettante says. Since the dawn of time, humans have deeply needed communal storytelling experiences. Cinema on the big screen is more than a business, it is an art form that brings people together, celebrating humanity, enhancing our empathy for one another — it’s one of the very last artistic, in-person collective experiences we share as human beings.”

- Denis Villeneuve, Director of Dune (2021), Blade Runner 2049, Arrival12

Quite the strong sentiment from Monsieur Villeneuve on the vital importance of theaters to film culture and the movie viewing experience. What informs such an impassioned statement? It is partly a response to the documented decline of movie theater attendance over the last several years. Much like the downward trajectory of cable TV, movie theaters during the first quarter of the 21st century confronted an audience changing how they seek out entertainment.

The numbers are pretty clear on this front. Movie theater admissions in the U.S and Canada reached 15.8 billion in 2002, the peak year in the 21st century for theater tickets sold. Adjusted for inflation, the U.S. and Canadian domestic box office for that same year (2002) reached $17.8 billion. For comparison, theater admissions in 2024 reached 760.5 million in the U.S and Canada, with box office returns hitting $8.6 billion. That’s roughly a 48% drop in ticket sales and domestic box office returns. Ouch.13

Note that this decrease in theater attendance and box office returns predates the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic theater shutdowns, one of the most traumatic upheavals to impact the film and television industry (not to mention the world at large, of course). Though that year proved a disaster, issues existed before then. The long-term downturn does, however, historically align with the increases in widespread digital media access, complemented by the ultimate ascendancy of film and TV streaming. These factors are not the only reasons for the recorded decline, but it is hard to argue with the fact that digital media and streaming have dramatically—and perhaps permanently—impacted theater-going behavior and box office return potential on a year-over-year basis.

Regardless, before the mid-2010s—when streaming services truly began to assert greater influence on the direction of film and TV—international film studios and distributors released a raft of great films spanning various genres and tastes. As one barometer to consider, when the New York Times published the top 100 films of the 21st Century, sixty-eight of the listed films were released between 2000 and 2015. The diverse range of cinematic achievements during this period is impressive, with films like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Mulholland Drive, There Will Be Blood, Spirited Away, Zodiac, Memento, Amélie, and Y Tu Mamá También (as well as many others) opening to audiences across a decidedly more globalized world.14 For those seeking blockbusters, sophisticated franchise filmmaking could be found in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, early Marvel films, and genre-bending thrill rides like The Dark Knight. Viewers could get their theatrical fix, whether they wanted arthouse fare, Frodo Baggins, or the Joker.

The period also saw the world's first entirely digital-enabled theaters installed in 2004, revolutionizing picture and sound quality with 4K definition, massive screens, and immersive audio systems.15 IMAX and 3D screenings became mainstream, offering experiences impossible to replicate at home. By 2009, 11% of box office revenue ($1.1 billion) came from 3D showings alone.16 It was the multiplex era, with complexes boasting 18-30 screens and offering 100-seat theaters as well as premium 400-seat immersive auditoriums.17

Despite these innovations, problems with the theater-going experience began to surface. Individual movie tickets could cost $10-20+ each per person (let alone if you threw any concessions on the bill), making frequent viewing expensive, especially for families on a tighter budget. Ticket buyers were also paying for a limited selection at a fixed location. At a turning point when cable TV served up over 100 channels and the internet seemed a boundless, depthless sea of content, most theaters showed only current releases with limited scheduling. And, similar to cable constraints, movie theaters required travel to specific locations at pre-determined showtimes, with no ability to pause, rewind or rewatch. You were beholden to one location at a set time in an otherwise digitally abundant and mobile world.

‘Cinema on the big screen as an art form that brings people together’ contended with a difficult question: what if people were beginning to value fundamentally different aspects of the movie-going experience?

Streaming Swoops In

All this is to say, when Netflix burst onto the scene with its online streaming service in 2007, the benefits seemed clear: unlimited streaming for a flat subscription cost (initially $8 per month for streaming-only plans!) with no advertisements and 24/7 access to an eclectic and international content library anytime, anywhere. Expensive cable bundles and theater visits would no longer be an issue. No equipment rental fees or long-term contracts. Reduced channel surfing and time waste. This was quite the user-friendly and streamlined experience compared to cable TV and movie theaters.

Notable shifts in film and TV development, production and programming took place at this time as well. With Netflix at the forefront, streaming services reeled in respected filmmakers and showrunners by offering them previously unheard of creative control to produce original, critically-acclaimed shows. In 2013, Netflix released House of Cards, a bona fide hit that officially announced the arrival of streaming on the doorstep of prestige television. Additional streaming hits like Orange is the New Black and Transparent solidified streaming as not just a player in the space, but as a brazen leader in both their approach to programming and how they addressed the entire audience experience. Online platforms like Netflix, Hulu and Prime Video, once treated as a sideshow by Hollywood power brokers, started to exert major influence across the entertainment industry.

Netflix and the early streaming services built on this success by introducing several advancements to revolutionize the entertainment delivery business model and on-service/on-platform user experience. Netflix's all-episodes-at-once release strategy dramatically changed viewing habits. ‘Binge-watching’ became a trend. With direct-to-streaming premieres, the company eliminated traditional theater windowing requirements and TV scheduling constraints. Established as a tech-first, digitally native company, Netflix employed viewing data and state-of-the-art algorithms to show that sophisticated analytics could help guide creative decisions and better tailor services to the subscribers’ specific viewing habits and interests (i.e., ‘personalization’), whether audiences were watching in living rooms or on their ever-present smartphones.18

The sway of legacy studios over the film, TV, and media elite began to flag. Major stars and directors increasingly moved from traditional networks to streaming. The success of originals such as the aforementioned House of Cards and global phenomenons like Stranger Things notably reduced streaming companies’ dependence on licensed content from other film studios and TV networks. Live event media providers and sports leagues, too, began to flirt with streaming services, airing shows and games as a preview of the more comprehensive and lucrative rights packages formalized in the years that followed.

In short, something of a paradigm shift was taking shape beyond mere adjustments to the mechanisms of production, distribution and exhibition. Film and TV were becoming more immediate and constant in everyday life.

Rise of YouTube: Wait…Is Mr. Beast really that ubiquitous and filthy rich?

During the initial growth of film and TV streaming, YouTube was concurrently founding an empire. Launched in 2005 and purchased by Google in 2006, the platform was the first globally available, completely free, user-driven video platform that enabled instant uploading, sharing, and discovering video content at scale. The service handled millions of daily uploads and views, quickly outpacing the reach and content diversity of traditional broadcasters. This effectively trained viewers to move from scheduled programming and physical media to on-demand digital video while simultaneously growing the careers of independent creators, influencers, and mainstream digital-first artists, thus establishing a whole new pathway for online entertainers and celebrities.

Then, in 2007, YouTube introduced ad-supported streaming. Creators could now monetize their content directly, and advertisers gained access to micro-targeted video audiences. This set the groundwork for bringing advertising (and its financial power) back to the fore of the viewing experience, while also creating a vehicle for independent creators on the platform to earn actual money outside of the traditional entertainment and monetization pipelines. A select few of these creators, like Mr. Beast and Jake Paul, amassed huge fortunes and significant cultural influence in the process. YouTube, in turn, gave rise to major linchpins of the modern streaming business: the previously non-existent ‘Creator Economy’ and the ‘Ad-supported Video on Demand (AVOD)’ model later adopted by various other streaming platforms.19

The platform’s technology, business model, and content variety set the standard for all subsequent streaming video services. This established YouTube as one of the more influential pioneers in digital media.

Streaming Meets the Ghosts of Cable Past

With the meteoric rise, early successes and business model contributions of platforms like Netflix and YouTube, the writing was on the wall: streaming was here to stay and changing everything in the process.

And, everybody wanted to be a part of it.

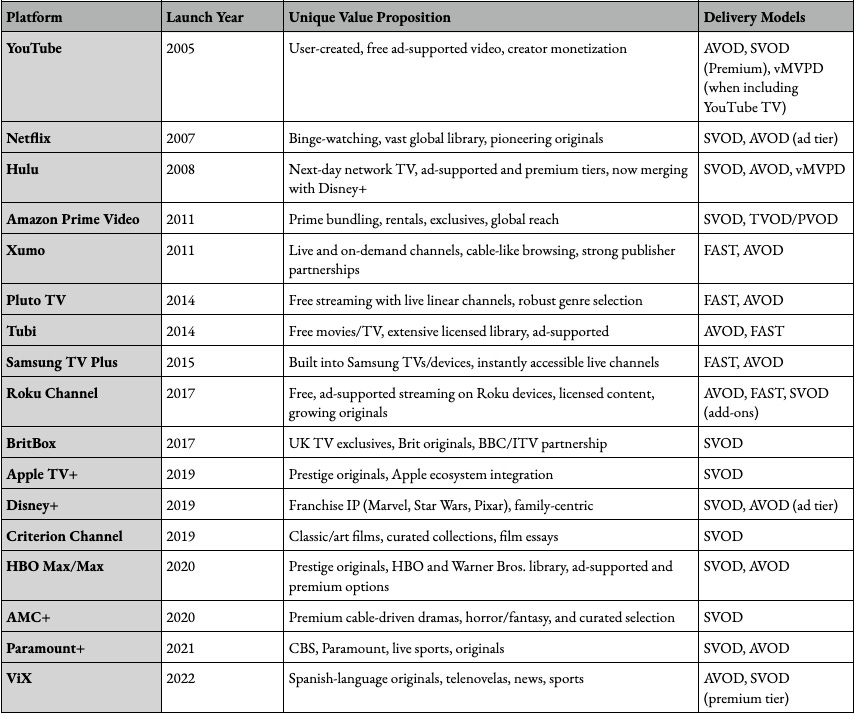

Competition for subscribers and views became fierce. From 2008 to 2020, major media, entertainment and big tech companies launched one or more streaming services, each promoting their own value proposition. As providers struggled to convince consumers that piling on subscriptions was worth the money, they positioned themselves as more affordable, having better programming, offering access to extensive libraries—or some variation on all of the above. Several companies accrued millions in debt to build these services. Platforms, like Hulu, Tubi and Samsung TV Plus, implemented the AVOD model initially pioneered by YouTube. The linear programming and advertising setup for FAST channels found its precursor model in, well…cable. The streaming wars were underway. Here’s a breakdown listing some—but by no means all—of the notable streaming service launches since 2005:

The onslaught of streaming services produced an entertainment delivery ecosystem that opened the door to a rich and extensive, if overwhelming, range of options.20 Monthly rates per service gradually began to fluctuate based on content demand and plan tier (i.e., ads or no ads). Inevitably, the bewildering accumulation of streaming subscriptions, models and options proved costly and confusing.

That brings us to where we are today.

It’s hard to miss the irony: monthly subscription bills have gotten out of control. Most platforms now offer ad-supported tiers. Even with streaming war winners like Netflix and YouTube drawing in more views than ever, content is still spread across numerous platforms to produce the same bundling issues that streaming aimed to solve. Sounds a bit like the old complaints against cable, no?

Full Circle Questioning

So, you can now get everything, everywhere, all at once…but it comes at a price. The willingness to navigate such complexity no doubt tests viewers' patience (and sanity). It is also no surprise that commentators raise alarms about market saturation and the need for consolidation. In response, media and entertainment companies are beginning to pursue mergers and acquisitions while plotting how to streamline content discovery and simplify payment.

But what do consumers and users really want? What platforms and models are indispensable for the future? Can the film and TV streaming revolution achieve its initial promise of a better entertainment experience and ecosystem? More on this topic in the subsequent entries of this series.

How do we make the party fun and easy to enjoy again?

What Else?

Stay tuned: With some vital background context established, upcoming entries will report on what audiences want from streaming and the prospects for the sector’s future.

Further reading: To think about streaming is to think about the attention economy writ large. The former is a subtopic of the latter—believing otherwise is foolish. Check out McKinsey & Company’s attempt to quantify the value of attention invested in different media and experiences. Strongly concur? Vehemently disagree?

Challenge: Consider what you most love and despise about the film and TV streaming ecosystem. I’m interested to hear from you whether 1). You’ve never known anything else (i.e., too young to remember using cable) or 2). You can compare the present-day entertainment experience to what came before.

Media intake:

– Books: Lonesome Dove (1985) by Larry McMurtry. Beloved by many. My first time reading. Some of the best character descriptions and dialogue I’ve ever encountered. I’m not a Western enthusiast, necessarily, but this novel works far beyond any genre preoccupations. The delicate and honest touch McMurtry applies to the sad sweep of the lethal, moony American West…quite something. And, ol’ Gus gets a nod for being one of the funniest, charismatic characters ever put to page.

– Small Screen(s): Grosse Point Blank (1997) directed by George Armitage. Revisited this sometimes forgotten piece of charming absurdity. Comedies once had no compunction about blending bizarre story premises and knife-sharp sardonic worldviews shot through with an unrepentant romantic streak. Peak Cusack(s). Minnie Driver as that-girl-you-fell-in-love-with-then-realized-she-wasn’t-real-but-shucks-she’s-great. Repartee worthy of 40s screwball comedies cut with 90s edge and filtered through 80s nostalgia. I’ve since been listening to Echo & the Bunnymen and wondering if I would survive a high school reunion (the answer is no).

– Big Screen: Seeing Weapons directed by Zach Cregger in the next few days. Hearin’ great things, and I love me some good Horror more than just about anything else. I’ll let you know.

Sources

"Media Streaming Market to Hit USD 108.73 Billion in 2025 Amid On-Demand Content Boom." Globe Newswire, 11 May 2025, www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/05/11/3078702/0/en/Media-Streaming-Market-to-Hit-USD-108-73-Billion-in-2025-Amid-On-Demand-Content-Boom.html.

"Streaming Reaches Historic TV Milestone, Eclipses Combined Broadcast and Cable Viewing For First Time." Nielsen, 17 June 2025, www.nielsen.com/news-center/2025/streaming-reaches-historic-tv-milestone-eclipses-combined-broadcast-and-cable-viewing-for-first-time/.

"Video Streaming (SVoD) - Worldwide | Market Forecast." Statista, 2025, www.statista.com/outlook/amo/media/tv-video/ott-video/video-streaming-svod/worldwide?currency=USD.

"Video Streaming Services Stats (2025)." Exploding Topics, 2025, https://explodingtopics.com/blog/video-streaming-stats .

"Streaming Services Statistics and Facts (2025)." Scoop Market, 2025, https://scoop.market.us/streaming-services-statistics/.

"Netflix Subscribers Statistics 2025 [Users by Country]." Evoca TV, 2025, https://evoca.tv/netflix-user-statistics/.

"YouTube Content Creator Statistics (2025)." Exploding Topics, 2025, https://explodingtopics.com/blog/youtube-creator-stats.

"Premium Video on Demand (PVOD): Definition." G2A News, www.g2a.com/news/features/premium-video-on-demand-pvod-definition/.

"Global Streaming Platform Partnerships: Telecoms, Bundles, and Growth Opportunities." BB Media, https://bb-media.com/streaming-platform-partnerships-telecoms-bundles-growth/.

Adgate, Brad. "The Rise and Fall of Cable Television." Forbes, 2 Nov. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/bradadgate/2020/11/02/the-rise-and-fall-of-cable-television/.

"Streaming Vs Cable TV Statistics: The Slow Demise of Cable TV." PlayToday, https://playtoday.co/blog/stats/streaming-vs-cable-tv-statistics/.

Villeneuve, Denis, director. Dune. Variety, 23 Apr. 2021, https://variety.com/2020/film/news/dune-denis-villeneuve-blasts-warner-bros-1234851270/.

"Movie Market Summary 1995 to 2025." The Numbers, https://www.the-numbers.com/market/.

"The 25 Best Movies of the 21st Century." The New York Times, 2025, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/movies/best-movies-21st-century.html#movie-10.

"Digital Decades: GDC Technology Celebrates Its 20th Year." Box Office Pro, www.boxofficepro.com/gdc-technology-20th-anniversary-dr-man-nang-chong/.

"Theatrical Market Statistics 2009." TechCrunch, Aug. 2010, https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/091af5d6-faf7-4f58-9a8e-405466c1c5e5.pdf.

Meissner, Christofer. "The Scale of the Screen: Auditorium Size and Number in the American Movie Theater." Media Fields Journal, https://mediafieldsjournal.org/scale-of-the-screen.

"Netflix's History Killed Blockbuster." Variety, 2025, https://variety.com/2025/film/news/netflix-history-killed-bl.

"History of YouTube - How it All Began & Its Rise." VdoCipher, www.vdocipher.com/blog/history-of-youtube/.

"List of streaming media services." Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_streaming_media_services.

— Note on Imagery: Unless I’ve provided credits for images in these posts, please assume they are generated by GenAI tools such as MidJourney, Gemini, and/or ChatGPT. I am not a designer or visual artist. An admirer, only. But I do enjoy concocting crazy-ass but relevant prompts, then reviewing and tweaking what the mighty engine delivers. With this said, I love to showcase the doings of flesh and blood artists. Send me a suggested work if you believe a particular artist’s contributions would be better suited to replace one of the generated images. These entries can certainly evolve. I will consider your request. Many thanks.

This is the end. More?

I have gravitated to the Amazon platform. I can find free items or pay for or rent many movies. I then add subscribed channels, currently Max, MHz (Babylon Berlin), Britbox and AcornTV. I like having the control of turning subscriptions off and on in ONE spot. Helps keep me sane.

My preference is to pay extra for ad-free and keep my subscription count low (max 3). The platforms with the best content (new, highly rated TV shows) will determine it for me. Still waiting on pick-and-choose your sport subscriptions. I would be willing to pay $30-40/month just for the premier league, but I don't want to spend $80/month for a full fubo/youtubetv.